NOW AND SOON AND SOMEHOW FOREVER

William Pettit and Candice Smith Corby

Center Street Gallery

Opened: June 16, 2023

Closing: November 26, 2023

Explore Museum Objects

Artists’ statement

Oh, I’m sailin’ away my own true love

I’m sailin’ away in the morning

Is there something I can send you from across the sea

From the place that I’ll be landing?

-Bob Dylan, Boots of Spanish Leather, 1964

This exhibition is inspired by the fundamental drive of whaling life; the poetics of longing. The prevailing sentiment beneath the thrill of the chase and the search for fortune; it is the beck and call of sea and home. Due to our own long-distance relationship across continents and an ocean, we deeply understand the concept of missing and reunion. After a long separation due to the Pandemic, we visited the New Bedford Whaling Museum in the summer of 2020 and were drawn to the intimate saga and the remnants of whaling life– of those who stay and those who come back, or never return.

During this same summer we began co-painting still lives of our New England meals of lobster and clams on our vintage dishes. We added a sliver of ocean with faraway land and suddenly a story emerged of a sea-faring captain missing home. This collaboration led us to draw inspiration from the museum collection; recreating and recontextualizing objects and images to create a dual-perspective installation featuring a Captain’s Quarters and a Lady’s Parlor. Both areas feature the pull of home and of the sea, the concept of distance and time embodied on the vast ocean and bridged by letters and objects. They tell a story of solitude and absence and the eternal yearning of love. Throughout the exhibition, viewers will find the element of gold; symbolic of love’s imperviousness to decay and its timeless luster.

The whaling enterprise was distinct in its constant flux of going away and coming back. Those who stayed and those who left were suspended in a state of longing for years at a time. From our personal experience and looking at the artifacts of the collection, we understand how dishes, shells, valentines, and handwritten letters became the thread that tied people together, in their time and across time. The power of objects to substitute and embody an absent love is extremely significant. A simple shell can recall a person, a voyage, act as an effigy, a talisman, or a souvenir. However, as in Dylan’s song,

No, there’s nothin’ you can send me, my own true love

There’s nothin’ I wish to be ownin’

Just carry yourself back to me unspoiled

From across that lonesome ocean

the thing will never satisfy the yearning of the other, but each lover knows that it will have to do for now.

Our back and forth of travel, of missing and being together, reflect the ebb and flow of whaling life, the tide, and time itself. Between geography and sentiment, exploration and settlement, there is the space of longing, a dream of the future and a nostalgia for the past, in this impossibly possible present: now and soon and somehow forever.

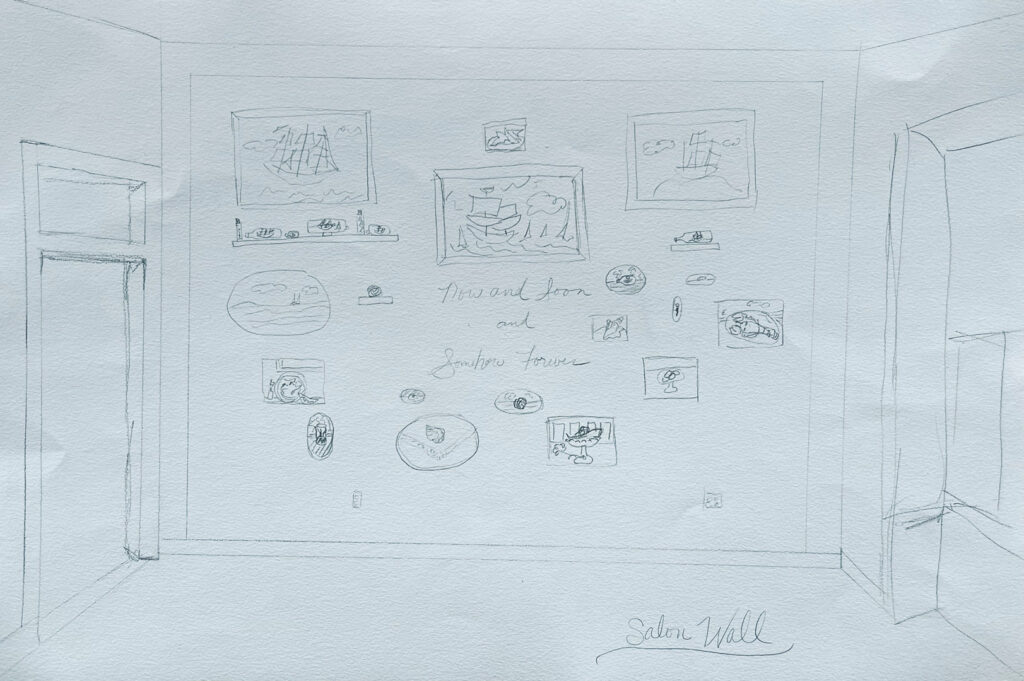

Salon Wall

This wall presents a mix of paintings and objects inspired by the museum collection. Our paintings, some individually made and some co-painted, directly reference museum objects and some pay homage to greater traditions such as messages and ships in a bottle, or shells being markers of one’s visit to a faraway place. While Pettit’s ships signal the majesty of arrival and departure, Smith Corby’s shells show the intimate beauty of quiet reflection; each shell links the holder to the sea and the unending voyage of waiting for a loved one.

Both Raleigh and Pettit painted these ships at the significant age of 50. After the golden age of whaling, ships were dedicated to bringing people together rather than taking them away. The passenger ship Veronica leaves the Azores with Mount Picu in the background.

See the original currently in the Bourne Building Balcony, in the “Voyage Around the World” exhibit.

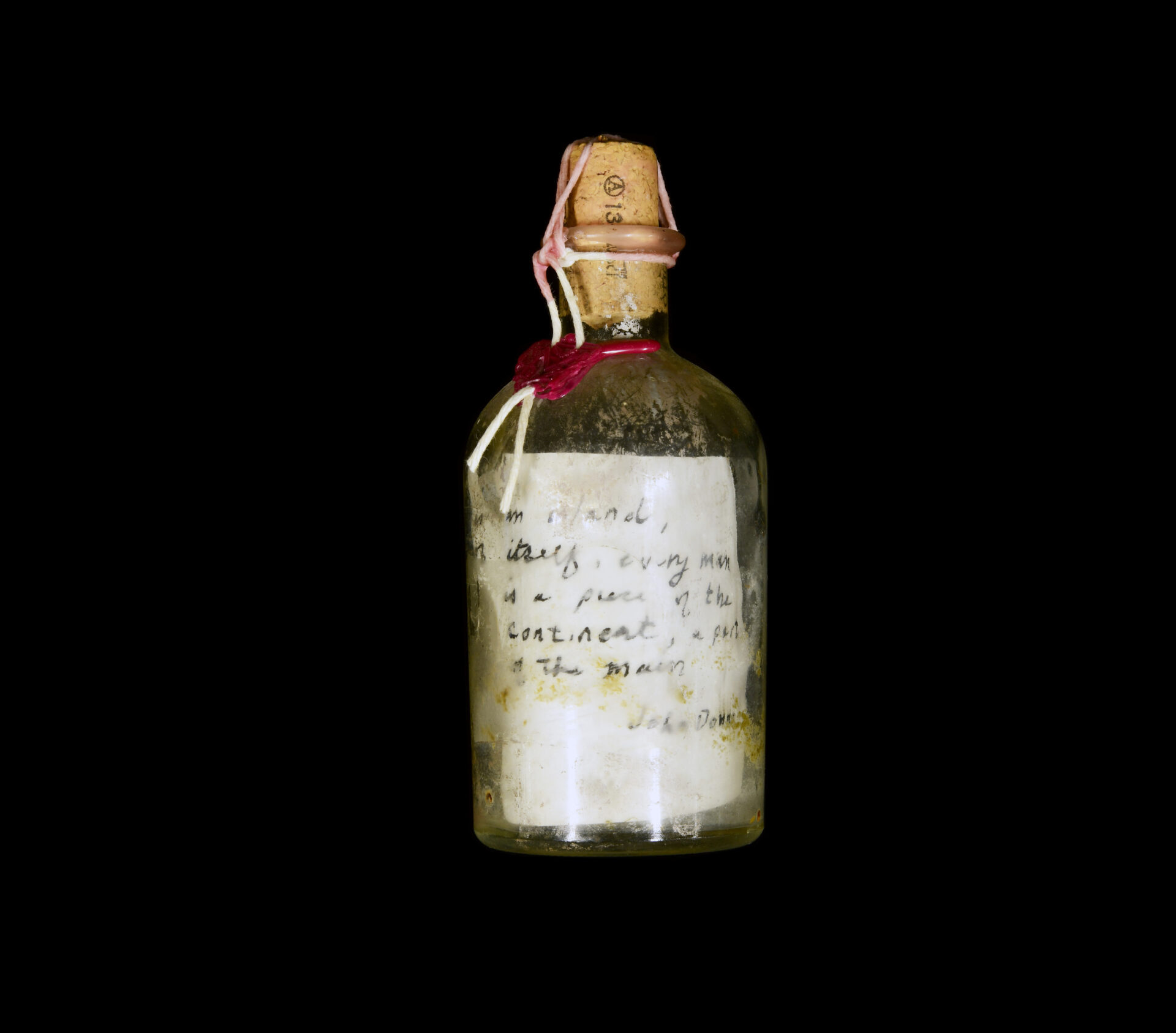

Co-painted by Pettit and Smith Corby, this ship against a field of red velvet brocade is captive in its domestic enclosure. The memory of a long past voyage is preserved and still upon a wooden sea. Similarly preserved, our Messages-in-Bottles are poems and love notes, sealed for an impossible journey through time and space.

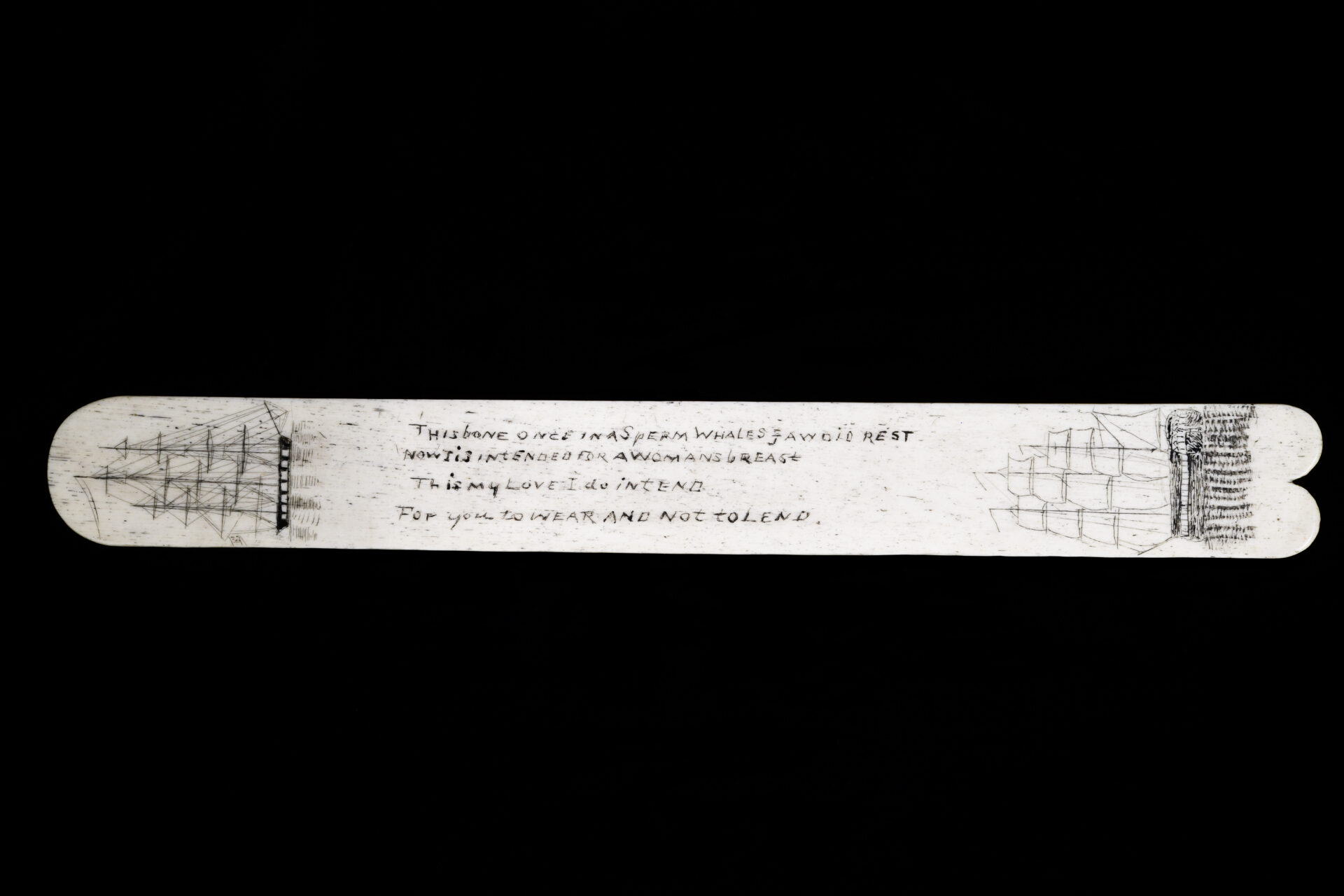

Our composition of personal objects speak to things collected and passed down over time. Our scrimshaw tooth, though beautiful, is not historic. Like the Museum’s busks featured in our Curiosity Cabinet, it is a memento of the past. Our Blue Willow patterned plate carries a lovers’ tragic story of forbidden reunion. Our painting Still Life with Lobster, in which a lobster with the sight of imminent land ahead is served on a platter, is similar to one hanging nearby from the Museum collection.

Decorative knot-making was common on long whaling journeys. The purpose of these was to show the skill of the maker as objects of beauty. A Turks head knot was used to mark the King’s spoke of a ship’s wheel, that showed when the rudder was in the central position. This mathematical intersection of lines that resembles the routes of whaleships is pulled together to become a globe, a resolution of longing. Ours holds a fleeting bloom.

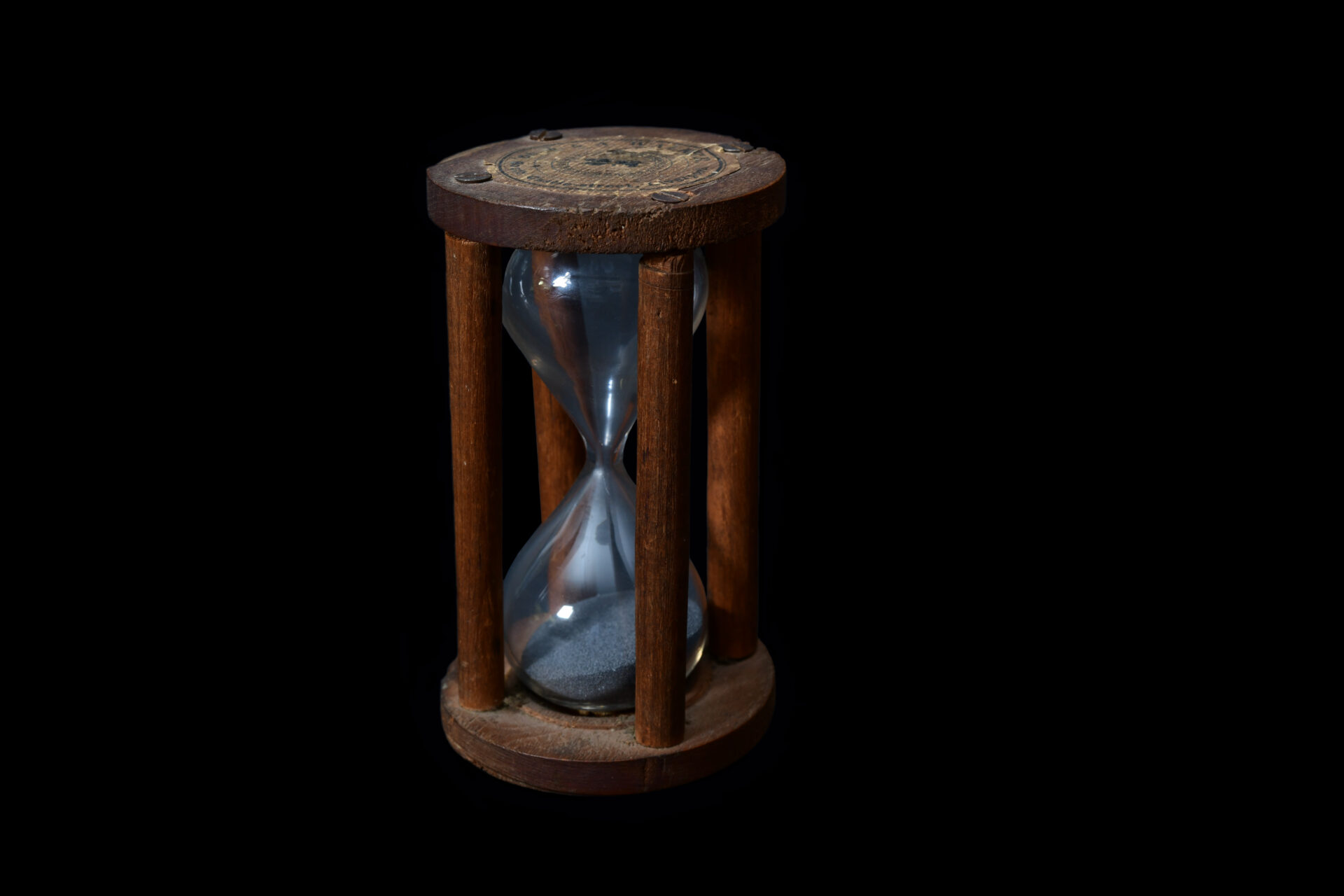

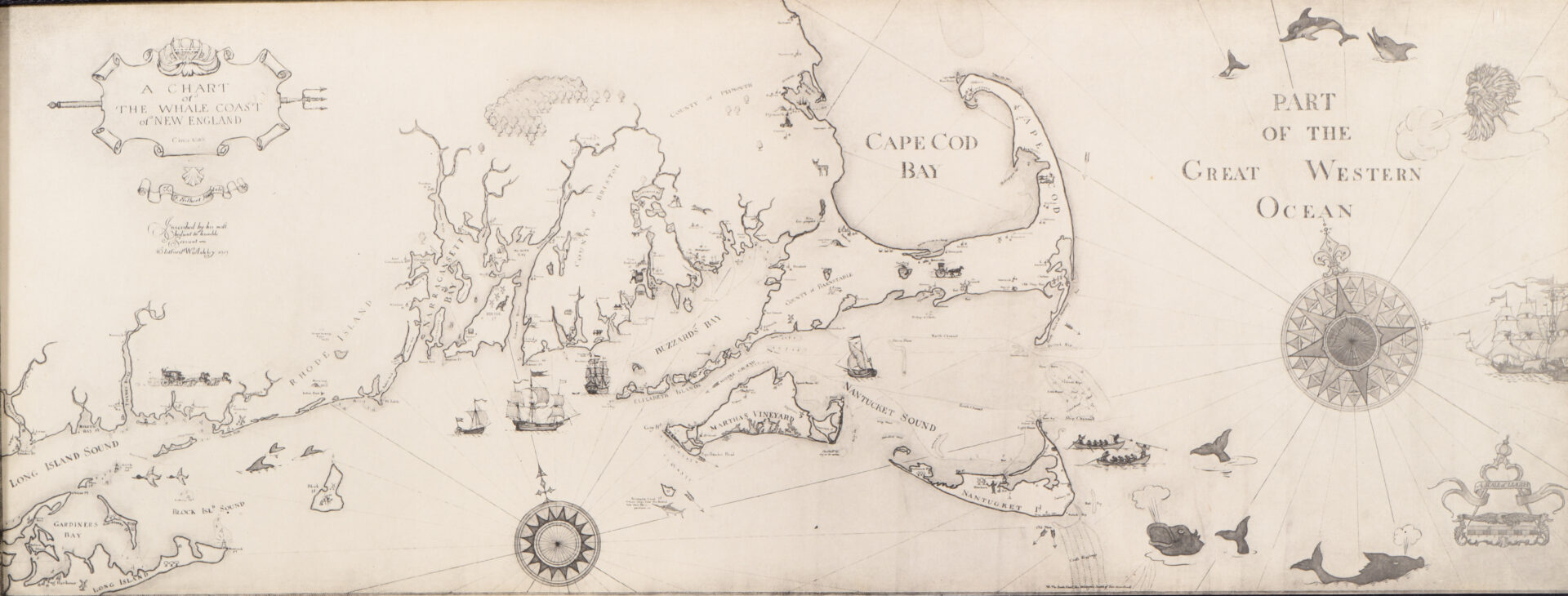

Long Distance

How do we measure the passage of time and space that separates us? By charts and stars, by minutes and years…wrinkles, knots, and weather. The museum items on display– an hourglass, a spy glass, pocket watches, a sextant, a map– are tools for navigation, for measuring time and space. They are equally objects of science and objects of art, crafted for beauty as much as for survival.

“Dearest,

It gets light and then dark, and the days expand between us. I count and measure minutes, seconds, infinitesimal time, the rhythm of water against the boards, the movement of a cloud. The days are long until we meet again.”

See our Hour Glass painting on the Salon Wall.

Message is an excerpt from MEDITATION XVII, Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, by John Donne.

“No man is an Iland, intire of itselfe; every man

is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine;

if a Clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe

is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were, as

well as if a Manor of thy friends or of thine

owne were; any mans death diminishes me,

because I am involved in Mankinde;

And therefore never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; It tolls for thee.”

Our artist-made messages in bottles are fictional expressions of loss and abandon, and desperate hope.

Unique examples of these are available in the Museum shop.

Knots bind together two parts, they secure the anchor and sails, they measure speed as distance divided by time. It is the intermingled arms and legs of bodies, forever close. Knots can be either order or entropic chaos; like a braid of hair or the entanglements of lines.

Of the many instruments of wood and glass, sextants and scopes that look ahead, clocks that measure the present, only the mirror, occupied with reflection, speaks of the past. It flips the landscape inward, from looking out to looking in, to what is behind rather than what is ahead. An instrument of vanity and introspection, it measures age and ageless beauty.

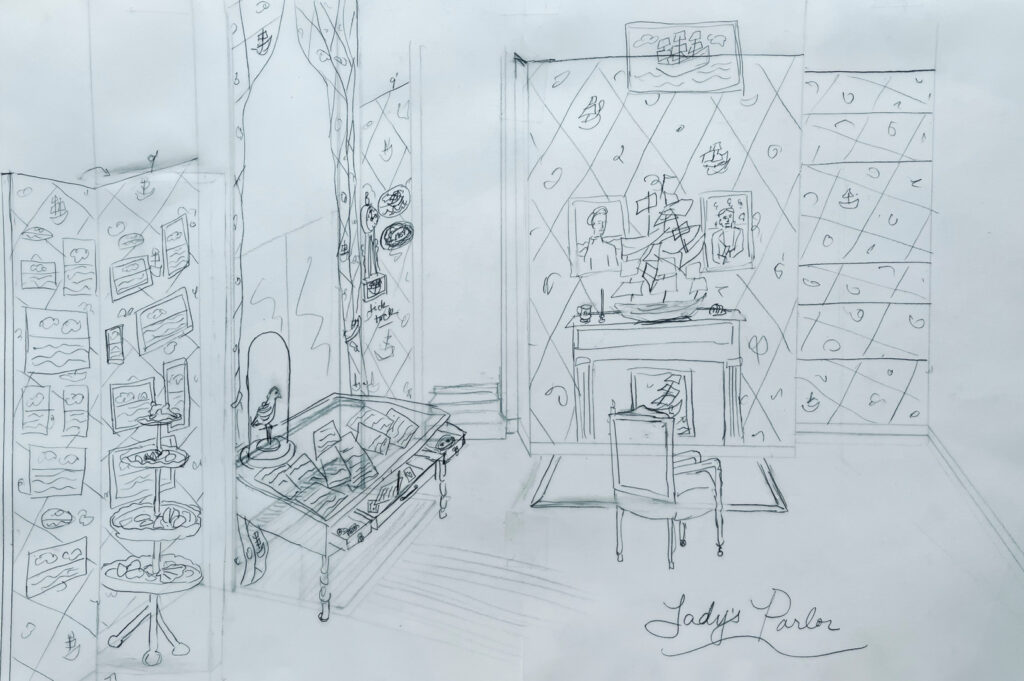

Lady's Parlor

Our domestic space features a writing area, hearth, and Curiosity Cabinet for the lady of the home. Her domain holds reminders of them, awaiting their reunion while also anticipating their inevitable goodbye. A place of reflection and full of anticipation.

The bespoke wall fabric indulges in the Baroque flourish of a wealthy Victorian home. A rope pattern delineates ships that alternately capsize and occasionally are lost to the fog. It is decorated with repeated symbols of longing: wishbones as talisman of luck, the conch for listening to the sea and calling out, and two love-birds over land.

She waits and watches. Hours become days and days to years. The sea and sky become one with no sight of his ship. Most of what he also sees, is nothing– the great expanse of water and air; sometimes indistinct- so that the line that divides carnal life and eternal transcendence almost disappears.

They both collect shells; whether from the beaches of Mattapoisett or of the Marquesas, near home or on a journey, clams and conchs and sea urchins and cowells, alone or engraved with a sunset over the beach, or made into elaborate valentines as the most simple souvenir.

See more shell portraits on the Salon Wall and vials of shells from a sailor’s valentine kit in the chest in Long Distance.

Our vintage banjo clock was inspired by the Roland Macy Banjo Clock in the NBWM Collection, we painted a reverse-painting seascape on the glass window. The clock is still working, and like the Roland Macy clock, it holds within it a history of waiting and counting.

See the Roland Macy banjo wall clock in Captain’s Quarters.

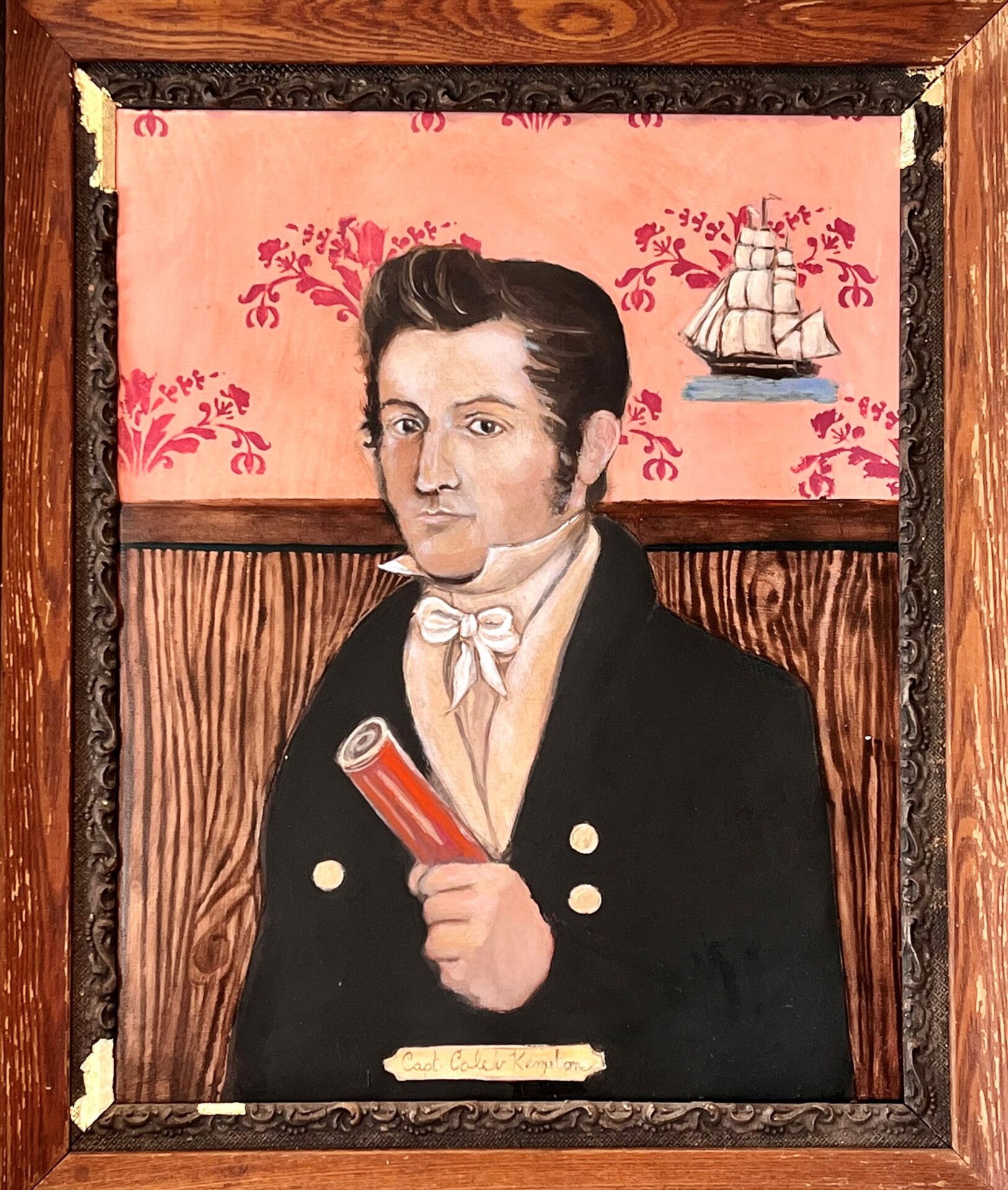

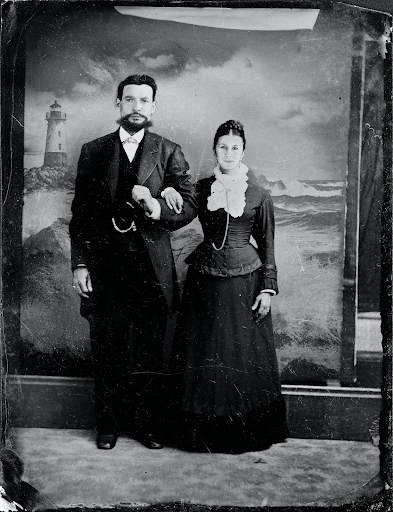

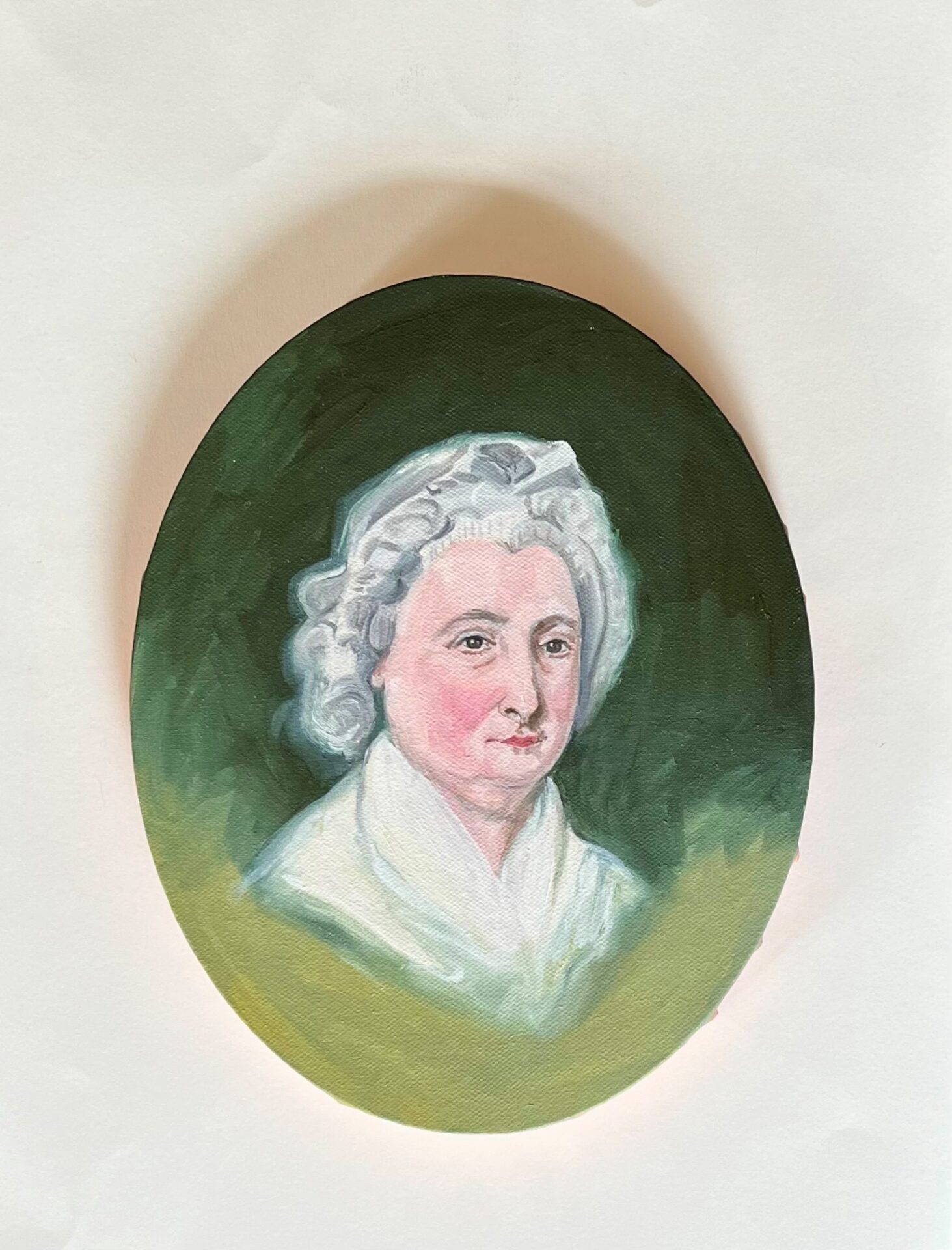

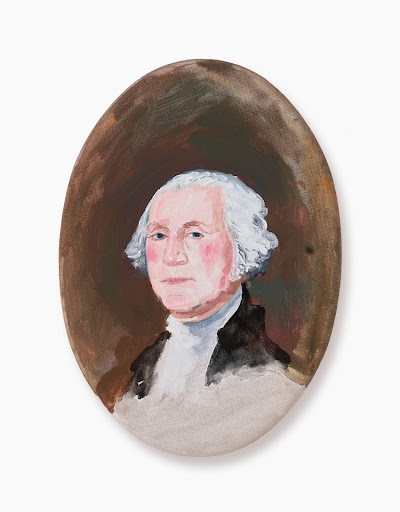

The symbol of togetherness and family, our hearth features paintings of Capt. and Mrs. Kempton along with a pile of broken gilded model ships. Our portraits are inspired by the Museum’s double portrait by Frederick Mayhew, however ours are physically separated. Mrs. Kempton’s background is a seascape, as the domestic space is invaded by the perils of the open sea, and the distance between her and her husband. Capt. Kempton’s floral wallpaper background signifies his endless wish to be home.

See the original double portrait by Frederick Mayhew in the Link Hallway and the Captain Caleb Kempton portrait in the Lagoda stairwell, as well as another version of our Mrs. Kempton in the Captain's Quarters.

Pettit’s ship paintings are meant to be an “homage,” to Bradford et al., as a respectful revisioning of style and technique. The taut stillness of sail and line act against the peaceful flux of sea and sky. East (right facing) ships are going out, West facing ships are coming home.

See the original painting by William Bradford on the Salon Wall.

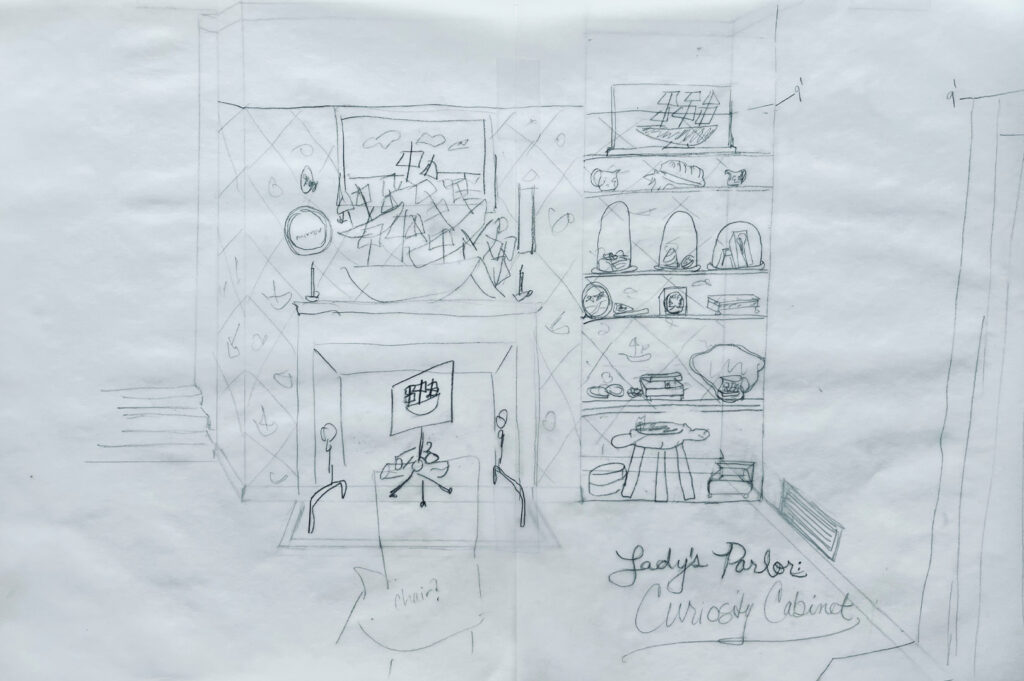

When not lost at sea, whaleships were scarred and broken by weather and whales. These models have been battered by time and neglect, in an act of forgetting, often relegated to attics and basements. Although they maintain signs of abandon, their gilded recovery symbolizes eternal hope.

See the Cased Ship Model from the NBWM collection at the top of the Curiosity Cabinet.

Lady’s Parlor: Curiosity Cabinet

Collecting as Recollecting: The tradition of the curiosity cabinet to display exotic and beautiful objects from around the world extended to whaling families. The objects collected by the long voyages of whaleships were accumulated and displayed in homes. These tokens of travel and symbols of status could be manufactured, like china and scrimshaw, or natural, like shells and bones.

Likely a souvenir from Australia, this egg would have been as exotic in a New Bedford home of 1850 as it is today. Inspired by the NBWM scrimshaw collection, ours shows two ships meeting, the logo of Now and Soon and Somehow Forever.

See a similar egg in the Scrimshaw Gallery.

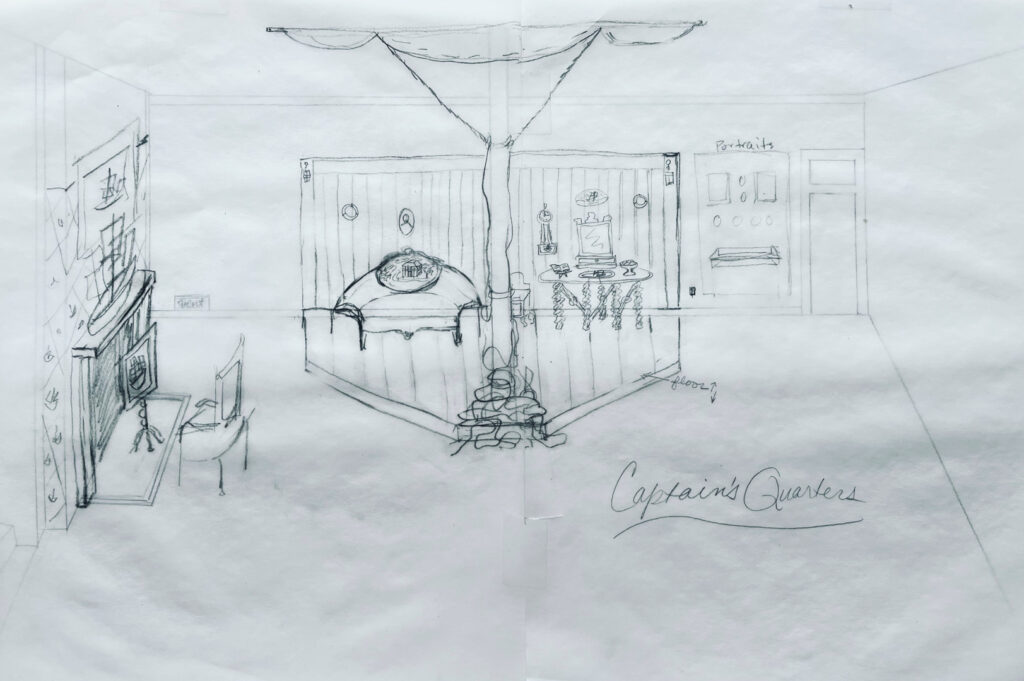

The Captain’s Quarters

The Captain’s Quarters recall the comforts of home while engaged in the outward actions of the hunt and survival. The artifacts of travel co-mingle with the reminders of home. Our “ship” rocks with the passage of visitors, accumulated ropes create a tangle, lamps flicker, and portholes peer out by reflecting inward.

As in our other portrait of Mrs. Kempton, her background is the sea, while Captain Kempton thinks of the comforts of home from his sofa.

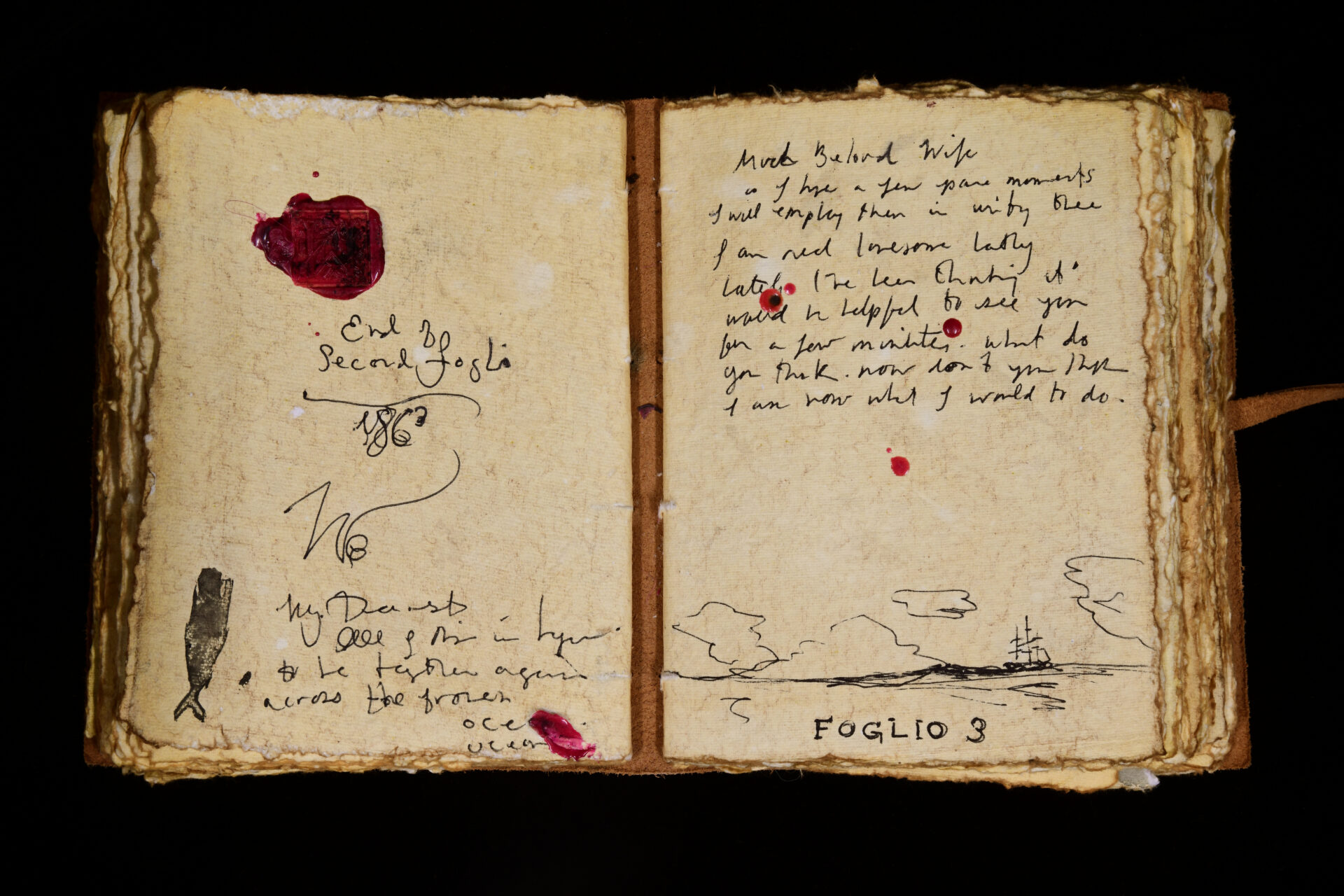

Our Captain’s log - or artist’s sketchbook, notebook, and journal, is based on letters, journals and logbooks from the NBWM library.

See the NBWM digital archive for many examples.

See our Banjo Clock rendition in the Lady’s Parlor.

The original painting from 1625, is a testament to the long story of whaling, and forecasts a rough and dark sea. As a counterpoint to the portrait of Mrs. Kempton who represents hope and safety, this painting represents the risk and terror of the sea.

Limes traded at ports along the South American coast were a valuable commodity to prevent disease like scurvy. The Captain’s privilege is displayed in an ornate dish.

See our painting on the Salon Wall.

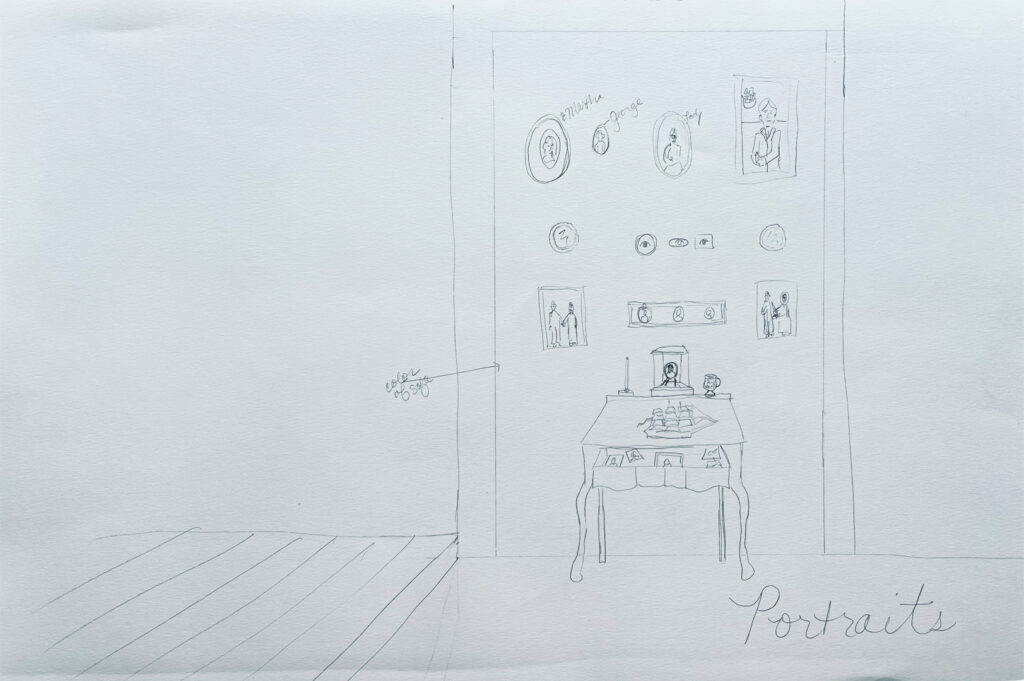

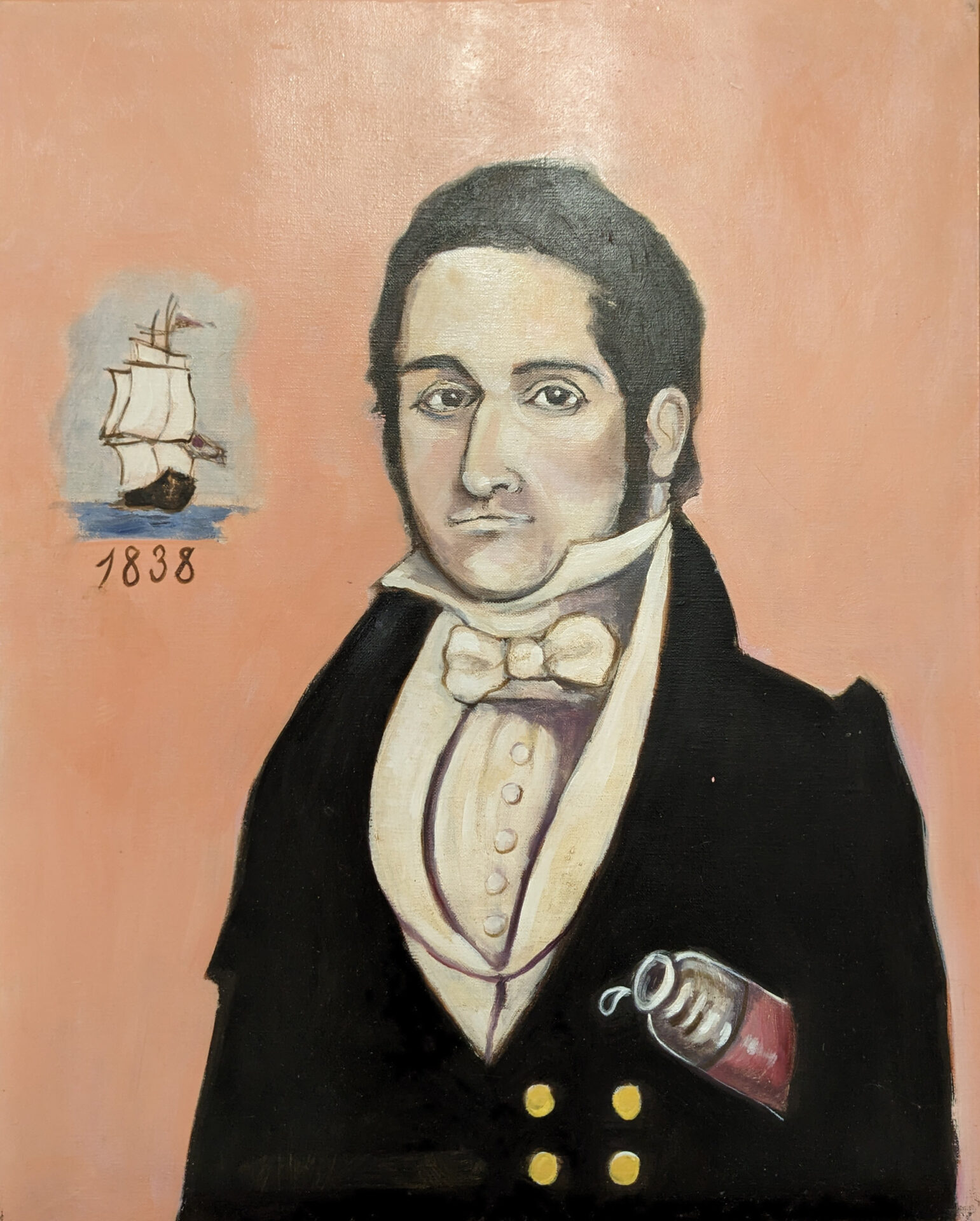

Portrait Wall

These portraits connect us to our individual and collective past. Some highlight the legacies of whaleships’ journeys and some simply are meant to remember that someone was special to someone. These were often portable, meant to keep close to one’s body and heart as a permanent presence. Itinerant painters and studio photographers made daguerreotypes, tintypes, ambrotypes, and paintings on canvas for every budget.

In a composite of the portrait of Manuel and Filomena Costa, the artists respectfully embody the identity of a whaling couple.

Ubiquitous in early American homes, a portrait of George and Martha Washington showed landowners’ political beliefs based on the principles of American colonies and identity.

James Townsend was both a captain and an investor. James Townsend was sadly lost at sea, never to return.

See the original by Frederick Mayhew, visible in the NBWM Lagoda Gallery Stairwell.

Whaling correspondence from the NBWM collection, read by the artists with instrumental interpretation of Bob Dylan’s “ Boots of Spanish Leather” played by William Pettit.

“The chime of hours is music, and your letters fill the sound with thoughts…I wind it each day, hoping to hear more of you…”