Communication and Social Behavior

Low and High Frequency

Social Structure

Social animals interact with each other in friendly and not so friendly ways. The patterns of these interactions over time reveals the kinds of relationships individuals have; are they friends or rivals? In turn, the pattern of social relationships, taking into account sex and kinship, reveals the social structure of a population. Some toothed whales, like sperm whales, have a very complex matrilineal (led by the females) social structure as females remain with their mothers and males leave home. Some killer whale populations have a very unusual social structure in that both males and females remain with their mothers as long as she is alive! In bottlenose dolphins, the strongest associations are between adult males. Such complex social structures have not been described in mysticetes. For example, gray whale populations, have no long-lasting associations or social cohesion.

Watkins Marine Mammal Sound Database

The William A. Watkins Collection of Marine Mammal Sound Recordings consists of recordings of various marine mammal species collected over a span of seven decades in a wide range of geographic areas by Watkins and many others.

General Communication vs. Echolocation

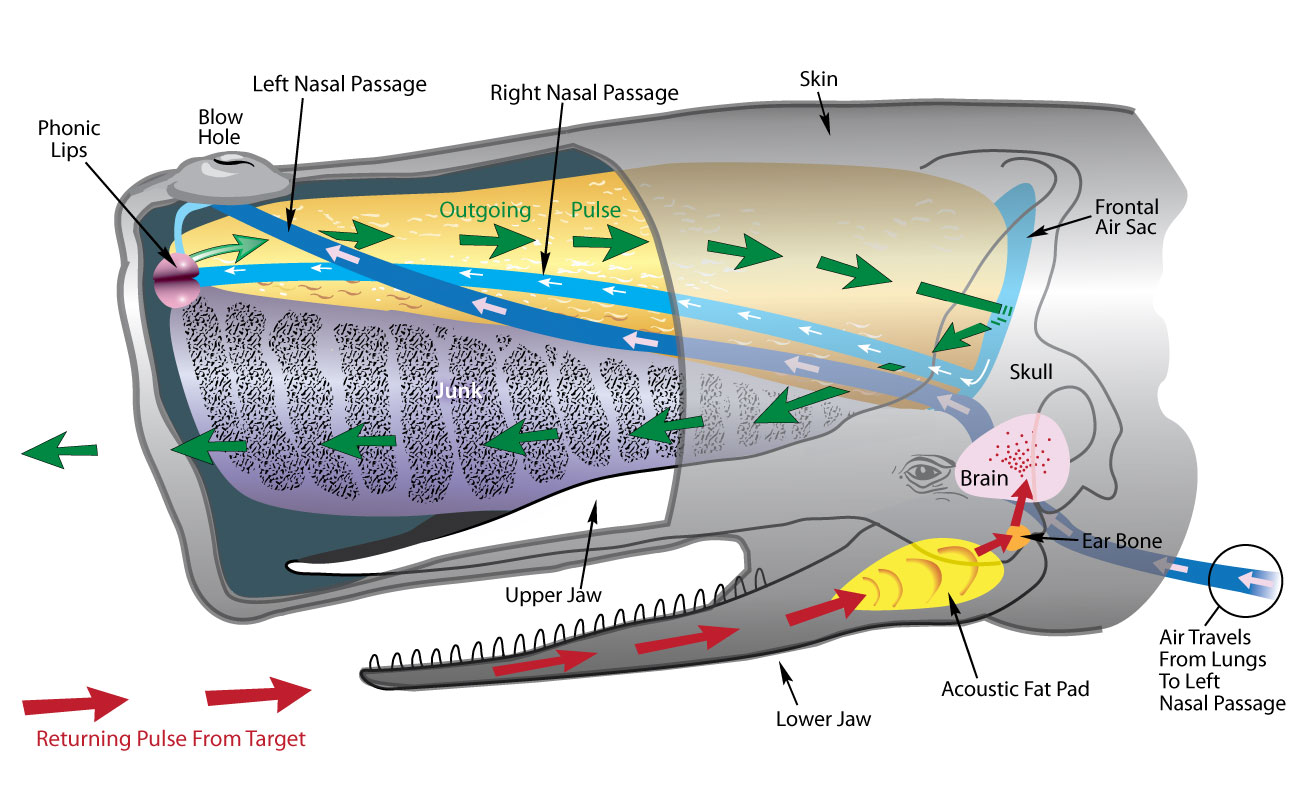

All cetacean species are able to communicate for a variety of purposes. This includes mothers and calves staying in contact, group hunting, animals finding each other over a large area, and males sending messages of aggression to other males. However, odontocetes are also able to create sounds to echolocate, so they can find food and navigate. All of this communication, including echolocation, is done without vocal chords. Exactly how this happens is still being studied, especially for the baleen whales.

Illustration Credit: David Blanchette, NBWM docent

Acoustic Habitat

Water is thicker than air, so sound moves much faster through water, approximately four times faster. The way that sound moves through ocean water is affected by the temperature, salinity (amount of salt) and depth (pressure). An increase in temperature, salinity and/or depth leads to an increase in the speed that the sound travels. But, these factors sometimes work a bit against each other. The surface is warmer than the deep ocean, but the pressure gets greater the deeper you go. So, figuring out the exact speed isn’t always easy.

One of the most interesting features of the ocean that relates to the movement of sound is a channel between 2600 – 3300 feet (800 – 1000 meters) that allows for sound waves, especially low frequency sound, to travel really long distances. But, it doesn’t travel as fast as at other depths. This is known as the SOFAR (Sound Fixing and Ranging) Channel. Baleen whales seem to be able to use this channel to communicate across ocean basins.

Breaching, Lobtailing, and Surface Behavior

Whales and their kin use a variety of forms of non-vocal communication to share messages with those around them. This includes fluke and flipper slapping, jaw claps, teeth gnashing, bubble emissions, breaches and tail and chin slapping. These behaviors help to indicate aggression, presence of food, presence of that individual animal, or a need for some space. The action of leaping out of the water, or breaching, is believed to indicate a heightened sense of excitement or presence of food. This action may also help get rid of parasites or loose skin.