Seals and Society

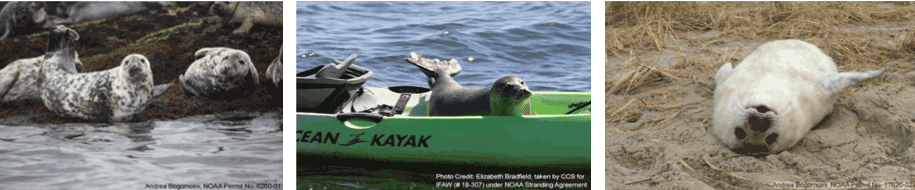

While many seal species use the waters off of New Bedford, harbor seals and gray seals are the most common and have a year-round presence in New England and beyond.

The Basics

If you walk a beach in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York and even south to Virginia, you may well see a seal. The two most common seals are gray and harbor seals.

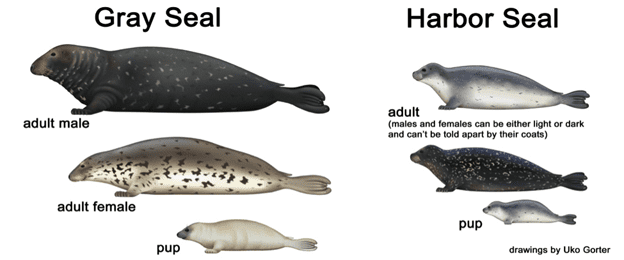

Gray seals are much larger than harbor seals, and the males and females look quite different. Adult males can weigh up to 800 pounds (females are about half that). Harbor seals, in comparison—both male and female—only weigh about 200 pounds.

If you look at the seals’ “noses” you’ll see that gray seals have more of a horse face while harbor seals have a slightly upturned nose. It takes a bit of practice, but once you’ve got the knack, it’s quite easy to identify seal species!

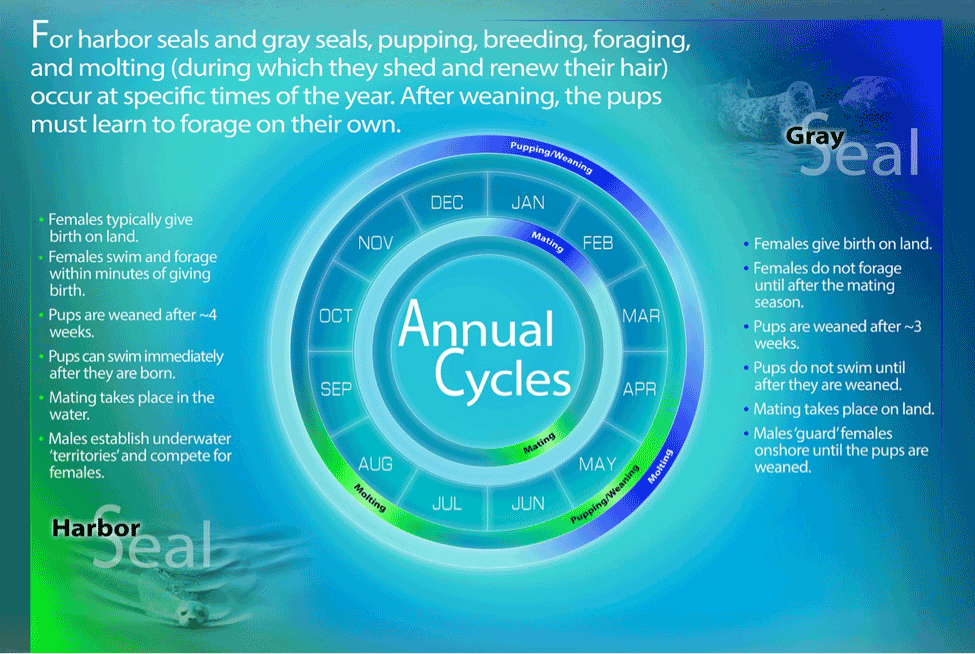

Although their ranges overlap in the eastern U.S., gray seals and harbor seals have quite different life cycles. The times of year when they give birth, mate, moult (replace their coats), and travel for foraging are distinct. Read on to learn more.

Seals at Sea

Seals, like whales and other marine mammals, benefited from the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act which protected them from hunting and harassment.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, there were literally bounties on the heads of seals. People in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine could turn in a seal nose and receive a payment from the state. That, however, was stopped in the 1960s when gray seals were protected in Massachusetts and in 1972, when we passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Today, seals are resuming their role in the ecosystem. The story of their recovery is still unfolding.

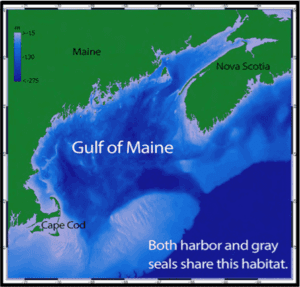

Gray and harbor seals have always lived in the Gulf of Maine and throughout the Northwest Atlantic. Archaeology tells us that seals have been important to people of this region for over 4,000 years.

By looking at “middens,” the places where people deposited their household waste, researchers have been able to see that coastal communities have always used seals. The details of that story are still being discovered today.

Harbor seals live across the northern hemisphere, in both the Pacific and Atlantic. Gray seals, however, are only found in the North Atlantic. There are three populations of gray seals that are genetically distinct: coastal North America; Iceland, the United Kingdom, Scandinavia, and northern Europe; and in the Baltic Sea.

Long-Range Swimmers

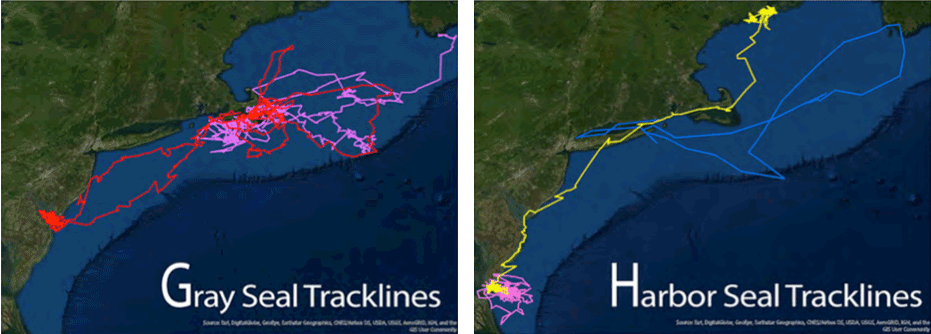

Gray and harbor seals can easily swim distances of several hundred miles—they can even sleep at sea. When we think about where seals “belong” we need to take a seal’s eye view.

Gray and harbor seals are both “phocids.” The three basic types of pinnipeds (seals, sea lions, and walruses) are the “phocids,” “otariids” and “odobenids.” The “phocids” have no external ear flap and swim by propelling themselves with their webbed hind flippers. The “otariids” have external ear flaps, like sea lions and fur seals, and swim with their front flippers. Walrus are the only living species of odobenid and are known for their prominent tusks.

Researchers have been curious to discover just how far a “normal” seal swims. While we do not yet have information from many seals, the animals that we’ve been able to put satellite tags on have taught us quite a bit.

What do they eat?

This is a question researchers and fishermen alike are curious to investigate.

Research shows that harbor and gray seals eat whatever is abundant locally, which changes with the season and their location. Sandlance, hake, haddock, squid, and flatfish are all part of their varied diet.

How do they find food?

It’s all in the whiskers. Seals have some of the most advanced sensory systems we know of.

Harbor seals’ whiskers (vibrissae) are so sensitive they can track prey under water from hundreds of feet away, even in the dark, by feeling currents and ripples created by swimming fish.

Seals have good vision, too, but often they are foraging in dark/murky waters. The importance of their whiskers can’t be underestimated!

Do they eat too many fish? What role do they play in our ecosystems?

Seals play important ecological roles in our oceans.

They provide nutrients both through their poop, which brings nitrogen to areas that need it, and as food for sharks and other predators.

Seals even eat predatory fish that, in turn, eat commercial fish species. Seals are sometimes blamed for declines in fisheries, but the full story is much more complicated. There are many researchers working on finding a way to tell the full story today.

Seals Ashore

Seals regularly “haul out”—come ashore to rest—sometimes in large groups and sometimes alone. This is normal and necessary. Watching seals at rest on the beach is a wonderful experience.

Gray seals, in particular, like to rest together in large numbers on shore. In summer, they have specific places where they like to gather at low tide. We call these “seasonal haul outs.” These locations are quite stable from year to year, and observing a haul-out of gray seals can be an amazing experience.

Imagine 400 or more gray seals resting close to one another, howling and moaning, wrestling and complaining. It is a sight as dramatic as any watering hole in the African savannah.

Seals will also come ashore to rest individually. Gray seal pups, in particular, can be quite comical. After they are weaned by their mothers at around 3 weeks, they lounge on shore, gaining strength and growing into their adult coat. That time ashore as a pup is critical to gray seals, because once they head out to sea, no one will help them or teach them to hunt for food. They must do it all on their own.

Be a good seal watcher!

If you see a seal on the beach, give them room to rest. Seals come ashore regularly, and it’s not unusual. But they need their quiet time!

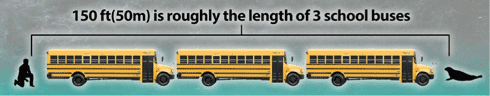

For your safety and that of the seals, stay at least 150 feet (50 m) away (roughly the length of 3 school buses), and do not touch or feed them. Keep pets on a leash.

For more seal watching guidelines, visit NOAA’s “Share the Shore” website.

Dive Deeper

If you’d like to read more, there are many resources:

- NASRC: The Northwest Atlantic Seal Research Consortium – a collaborative group that focuses on research, education, and citizen science in the East Coast of the US. Their mission: Working collaboratively to improve our understanding of the ecological role of seals in the Northwest Atlantic. The seal FAQs are particularly helpful.

- NOAA gray seal page: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/gray-seal

- NOAA harbor seal page: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/harbor-seal

- Center for Coastal Studies Cape Cod seals page: https://coastalstudies.org/seal-research/cape-cod-seals/

- Watkins Marine Mammal Sound Database: Hear what seals in the Northwest Atlantic, such as harp seals and bearded seals, sound like: https://cis.whoi.edu/science/B/whalesounds/index.cfm