Research

Whale Information Bibliography

A suggested list of books and selected articles:

Books

Among Giants: A Life With Whales

Charles ‘Flip’ Nicklin, 2011, University of Chicago Press

Cetaceans: Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises

Mark Carwardine, 2002, Dorling Kindersley Publishing

Humpback Whales

Philip Clapham, 1996, Voyageur Press

Sperm Whales: Social Evolution in the Ocean

Hal Whitehead, 2003, University of Chicago Press

The Book of Whales

Richard Ellis, 1980, Knopf Press

The Great Sperm Whale: A Natural History of the World’s Most Magnificent and Mysterious Creature

Richard Ellis, 2011, University Press of Kansas

The Urban Whale: North Atlantic Right Whales at the Crossroads

Edited by Scott Kraus and Rosalind Rolland, 2009, Harvard University Press

Whales and Seals: Biology and Ecology

Pierre-Henry Fontaine, 2007 Schiffer Publishing Ltd.

Whales in the Classroom: Oceanography

Larry Wade, 2001, Singing Rock Press

Meet the Whales

Larry Wade, 1995, Singing Rock Press

The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Sea

Philip Hoare, 2010, Harper Collins

Selected Articles

Fin Whale at Feeding Time (Carl Zimmer, NY Times 12/11/07)

How Ancient Whales Lost Their Legs, Got Sleek and Conquered the Oceans

Hear That? Bats and Whales Share Sonar Protein

Learning from Whales and Whalers on Top of the World

Emptying the Oceans: A Summary of Industrial Whaling Catches in the 20th Century

In 2014, New Bedford Whaling Museum’s Director of Education and Science Programs, Robert Rocha, was the lead author on this report published in NOAA’s Marine Fisheries Review. The report was the first to combine corrected totals for illegal Soviet whaling with International Whaling Commission data, to provide an accurate, and sobering, reporting of the number of whales killed in the 1900s.

Studying large animals that live in water, that don’t spend much time at the surface, that don’t speak a human language, that may live far offshore, that are capable of traveling long distances and diving deeper than 5,000 feet (1500 meters), and that could kill you or sink your boat with one flick of its tail, is not easy.

Yet, people have been trying to learn about these creatures for thousands of years. Aristotle wrote about them over 2,000 years ago. A text called Speculum Regale, published in Norway around 1250, talks about cetaceans along the coast of that country. Olaus Magnus’ Carta Marina (Marine Chart), from 1539, shows whale-like beasts in the oceans of the world.

Despite all of these challenges, the study of whales, dolphins and porpoises continues on a daily basis. This research can take several forms…

Organizations Involved

Research on these animals is performed around the world, by scientists at universities, private institutions, government agencies and the military. The United States Navy has been supporting this type of research since the 1940s. Being able to distinguish between a large whale and a submarine when you are hundreds or thousands of feet below the water surface is very important. Locally, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), New England Aquarium, and University of MA – Dartmouth, are three of many entities performing research on various aspects of the lives of cetaceans.

Bioacoustics

Understanding how sound moves through water, and how animals like whales make use of that sound throughout their lives, makes it easier for us to increase our knowledge of their daily lives. The field known as bioacoustics (biology and acoustics) is the study of how animals use sound, especially for communication.

Recording of marine mammal sounds began in 1949 when Dr. William Schevill, from WHOI, recorded a beluga whale in Quebec’s Saguenay River. (You can view a vinyl pressing of this recording in our new exhibit.) In 1958, Dr. William Watkins joined Dr. Schevill and for forty years they created new equipment, made thousands of recordings, and changed the ways we listen to and study marine mammals.

The New Bedford Whaling Museum is now home to the entire catalog of marine mammal recordings that was compiled by Dr. Watkins. This collection includes dozens of recordings made by other researchers. We also now own many of the tools, recording devices and notes that Drs. Watkins and Schevill used in their research. This generous gift from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution was donated in 2014. Some of it is in use or on display in this exhibit.

Boat-based Observation

If you are lucky enough you may get to see a whale or a pod of dolphins from the shore. Most of the time, however, you have to go to them. Typically, boats are used as the platform of observation. Research vessels come in all shapes and sizes. Some trips last a few hours, some a few weeks. Marine mammal observers normally go out on whale watch vessels so they can catalog whales seen on each trip. Some do their observations on fishing boats. Some researchers have the training and the proper paperwork that allows them to dive into the water with these animals, record video, take notes and collect samples. Another useful aquatic research tool is an Automated Underwater Vehicle (AUV) that can be programmed to follow a specific course and record data.

Aerial Observation

Research can be done from the air. Low flights over breeding grounds of right whales make it possible to count mother and calf pairs. Drones are being used to film rarely seen behaviors, such as nursing. Drones also take photos and collect the air that whales exhale so it can be tested in a laboratory for stress hormones and other factors.

Whalers’ logbooks and diaries

Captains and first mates on whaling ships kept a daily log of all activities during a voyage. These entries included latitude, longitude, weather, whales seen and hunted, other animals that were seen, and places visited. Several men had journals that included personal information. They didn’t know it at the time, but this information would become a historical record of the conditions and populations of the places they visited. This data can be compared to current conditions.

Necropsy and specimens

Because whales and their kin are hard to study, it has proven useful to do a complete study of each cetacean that dies. This investigation, which includes length and width measurements, analysis of stomach contents, and reports of bruising or fractures, is called a necropsy report. Sometimes the information learned from the body of a dead whale, such as the cause of death, can be used to save living whales. Necropsy Sheet (pdf)

Tagging

Photo Credit: Robert Rocha

Tags can be attached to whales for a short period of time to collect data. Some are fired into dorsal fins and shake loose after weeks or months. Most are attached via suction cup to the backs of the animals. These digital tags (DTAGs) have gotten smaller over time yet record more data. This information includes depth, pitch, roll, speed, interactions and temperature. This data can be translated by software like TrackPlot into an animation of the animal’s activities.

Biopsy Darts

Photo Credit: Monica Zani, New England Aquarium

A biopsy dart is a slightly hollow tip that is attached to front of an arrow. The arrow is fired from a crossbow, strikes the whale, takes a sample, falls off the whale, floats in the water and is retrieved by researchers. The tip is unscrewed from the arrow. The sample is removed and then analyzed by researchers for genetic, health, and contaminant studies, as well as cell line cultures.

History of Knowledge

Cetaceans are hard to study, but they have drawn our attention for thousands of years:

- Aristotle made careful observations and wrote about cetaceans more than 2,000 years ago in Historia animalium.

- Most of our early knowledge of cetaceans was based on examination and drawings of animals that washed ashore. These animals were in different states of decomposition.

- Edward Tyson, a British scientist, in 1680, was the first to focus on cetacean anatomy (primarily a porpoise brain) in research dedicated solely to that purpose.

- It wasn’t until 1758 that written classifications stated clearly that cetaceans were mammals. Strangely, in Moby-Dick, published in 1851, Melville refers to whales as a ‘spouting fish with a horizontal tail’.

- Thomas Beale, a British surgeon who accompanied whale hunts in the South-seas, published the first thorough report on sperm whales in 1835.

- Discovery Reports are the result of 33 years (1918-1951) of meticulously recorded data of British whaling in Antarctica.

- Biologists on board industrial whaling vessels of many other countries conducted their own biological studies. Included in this group are Soviet biologists who did the studies and secretly kept accurate catch numbers in the mid-1900s, in defiance of their own Communist government.

Watkins/Schevill Collections

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) has gifted marine mammal data and artifacts to the New Bedford Whaling Museum. There are two components to this gift. The William A. Watkins Collection of Marine Mammal Sound Recordings and Data consists of Watkin’s data set, audio and video recordings, papers and reprints. The William A. Watkins and William E. Schevill Collection of Images and Instruments consists of photographs, recording instruments and harpoons. These collections were created or collected by William Alfred Watkins, with the assistance of William E. Schevill, Peter Tyack, Melba Caldwell, Thomas Potter, and G. Carleton Ray, among others.

Historic Marine Mammal Sound Archive Now Available Online

Click here for access to recordings of more than 60 species.

The William A. Watkins Collection of Marine Mammal Sound Recordings consists of recordings of various marine mammal species collected over a span of seven decades in a wide range of geographic areas by Watkins and many others.

Read a News Release about the online Marine Mammal Sound Archive. (6/20/2016)

WHOI finding aid offering a fuller description

Transcript of interview with William A. Watkins by Gary Weir and Frank Taylor (pdf), March 2000

About William Alfred Watkins

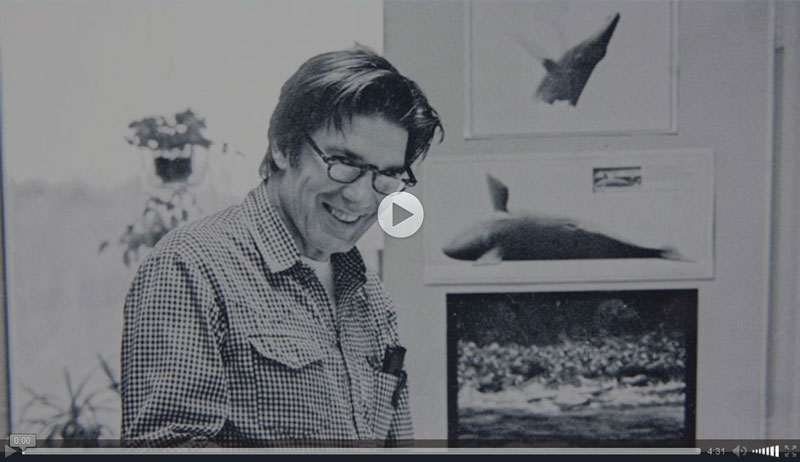

Below: a 4 minute video featuring William A. Watkins titled The Man Who Opened Our Ears to the Ocean.

William Alfred Watkins was a pioneer in marine mammal bioacoustics, studying the acoustic behavior of whales, dolphins, and seals in their natural environments. He was born January 8, 1926 in Conakry, French Guinea in West Africa, where his parents worked for the Christian Missionary Alliance Mission. After receiving a B.A. degree in anthropology from Wheaton College in Illinois in 1947, he worked on the college’s staff in electrical and radio systems until 1950 before returning to West Africa, where he was born and raised. Interested in linguistics, he mastered more than 30 African languages. He built and operated an international radio station (ELWA) in Monrovia, Liberia from 1951-1957. He also served as President of the West African Broadcasting Association, and was station manager and language department chief of ELWA before moving back to the United States and Cape Cod.

Marine Recordings Locations Worldwide

Below: Geographic Location of Marine Recordings Preserved in the William A. Watkins Collection of Marine Mammal Sound Recordings and Data.